Kristiana Kahakauwila

Interview by Michael Kelley

Interview by Michael Kelley

My first impression of Kristiana Kahakauwila was formed via e-mail in June of 2011, a few weeks after I arrived in Hawai`i for the first time. I had been hired to teach English in a summer program at Chaminade University of Honolulu, and Tiana, as I learned her friends call her, was the other English instructor. I was new to the program, so I e-mailed her and asked if I could borrow from her syllabus. She wrote back something along the lines of, “Oh yeah. Have at it.” Many people are territorial with their ideas, but Tiana was completely (and unnecessarily) gracious. I immediately presumed that I would enjoy working with her—and, as it turned out, I was right.

I have enjoyed all my summers in Hawai`i—who wouldn’t?—but that first one was special, as the first visit to a new place always is. A huge part of that was working with Tiana. We had similar ideas about what our students needed in order to learn, succeed, and move forward. We had mutual interests besides: the ocean, of course, but also books and film and restaurants and a good glass of wine. We were both curious about the shadows of life where so many of us linger, and where writers find so much of their material. When we discovered that we both wrote creatively, I suggested that we trade stories. I brought in a quixotic piece about a man who builds a large wheel, which he uses to scribe gloomy literature quotes; Tiana showed me a draft of “Portrait of a Good Father.” As anyone who has read this story can imagine, I was blown away by Tiana’s lyricism and insights into humanity. I remember telling her that she possessed a novelistic point of view: her characters achieved great depth, her plot was subtly labyrinthine, and her story both embraced the island setting and transcended it. As the New York Times review aptly put it, “This story could have been set anywhere.”

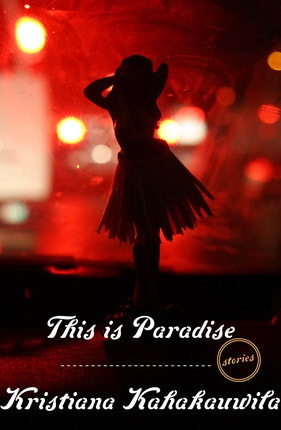

It is easy to parse Tiana’s work by the ideas that are immediately identifiable: the power of voice, images of the feminine, the mysteries of identity, the exploration of multidimensional sensuality, and, of course, the unique culture of island life. But what makes these stories especially impressive is the seemingly effortless weaving of all these attributes into one magnificent fabric. Pull one thread, and the entire tapestry feels the tug. Step back and take in the whole project, and, as with impressionist art, the designs and colors tempt us to forget that there is any conscious artistry at all. It was exactly this “conscious artistry” that impelled me to ask Tiana for an interview, to which—as is her character—she generously agreed. Also in character, Tiana responded to my questions with a candor and acuity that will help us all in gaining and even deeper appreciation for This is Paradise: Stories—and, no doubt, her books still to come.

Michael Kelley: Your stories include sensual details that move beyond the visual. Was the attention to sensory impression a learned skill or instinctual?

Kristiana Kahakauwila: A little of both. Even as a child I paid close attention to the way the world smelled and tasted and felt. I love the tactile aspects of a meal and support playing with one’s food. I recognize people close to me by their scents, and I’m aware when their scents change. But the ability to translate these sensory experiences into language, especially language that will mean something to a reader, is a learned skill. When I was working at Wine Spectator magazine I was taught how to put the scent and taste of a wine into words, and then to also describe the texture of the wine, and finally to recognize its visual aspects. Those lessons, taught in that order, have proved endlessly useful to me in my fiction writing.

Michael: You now teach creative writing at Western Washington University. Can you tell us a little about the relationship between your writing and your teaching? Does one influence the other to any degree?

Kristiana: Every time I teach an aspect of the fiction-writing process, I have to re-think the craft of telling story. If I’m teaching a lesson on character development, for example, I lecture on how I create a character as well as how other writers approach this task. I choose several published stories for my students to study. I also ask my students how they get to know their characters, and I give exercises to help students better understand and motivate those characters.

At the end of the day, when I go back to my own creative work, I have all this—the published stories, the close study, even my own lecture—helping me re-imagine one aspect of craft. Even more than all that, though, I’ve spent the day with my students’ questions, their debating, and their counter-examples, and it’s their engagement that does the most work in refining my writing process and making me sharper.

I also love the opportunity to teach graduate students, which is more like a sustained dialogue on craft than a formalized lecture. Western just changed their MA in creative writing to an MFA, and the program’s ability to mix literature-focused MA students with creative writing MFAs means seminars are especially vibrant. And, again, I come away from those courses with new ideas for reading and writing.

Michael: Though I have spent three consecutive summers on Oahu, and I feel comfortable in that community, reading This is Paradise frequently made me feel haole, that is, foreign to a place I think I know well. I wonder if you think that this distancing phenomenon can be overcome. Where do you think your literature, and perhaps the work of other Pacific writers, leaves a reader who is not native or local?

Kristiana: Writers of any literature must make a decision about how much they wish to inform their readership about the social mores, the cultural norms, the history—in other words, the world—of their book. Patricia Grace is on one side of the spectrum. She gives very little background. Her novel Dogside, for example, drops the reader in the middle of a Maori seaside town and one spends the next two chapters catching up on the political forces at play. Via this technique, Grace underlines the differences between the reader and the Maori community, and she then uses this tension and cultural difference as a driving force for the plot and central theme of her novel. By contrast, Robert Barclay’s Melal, which takes place on and around the Marshallese island of Kwajalein, has to explain the complicated history of U.S. atomic testing on those islands in order for the reader to understand the significance and action of the story. Barclay doesn’t want his reader to feel distanced from this history; he wants the reader to feel the emotional impact of the US’s role in that history.

To me, that distancing phenomenon you describe is essential to the experience of reading This is Paradise. First, the Hawai`i in This is Paradise is not the Hawai`i of brochures and travel magazines. Its beauty comes from the land and ocean, sure, but also from `ohana, the act of survival, commitment to one’s community, the way history echoes into the present. So I purposely wanted to take the reader’s expectations of this place and its culture and turn those expectations on their head. That’s a distancing experience for a reader.

Second, the characters in the book are often distanced from themselves, sometimes by the choices they’ve made and sometimes by the way the world operates around them. I want the reader brought into that tension. I also think that the distancing effect on someone who is unfamiliar with Hawai`i and its cultures isn’t a bad thing. Often we travel or visit new places in order to feel outside ourselves; reading can have a similar effect on us. By being brought outside ourselves for a while we then expand how we see ourselves. Our world, and we, become larger.

Michael: The short story “This is Paradise” offers a trio of perspectives, all female, all written in the first person plural. Why choose to use the “we” perspective?

Kristiana: The “we” perspective was an opportunity to think about how groups of women might be influenced by age or socio-economics, as well as what might unite them. In the story the career women have one set of concerns, the surfer girls another, and the Micronesian hotel maids a third. At first, each group responds differently to Susan, a tourist in Waikiki. But when that tourist is harmed, all three groups of narrators are sorry they didn’t protect her more. When they are no longer divided by their personal concerns, their common humanity emerges.

In addition to this, the “we” perspective implicitly includes the reader, and the reader becomes part of each group of women. So a story that at first appears to be about how different locals are from visitors ends up emphasizing what makes us—characters, readers, narrators—similar.

Michael: Your response immediately triggered a memory. Three summers ago we were at a lanai party, and some uninformed young man, a stranger to both of us, went on a tirade about the uselessness of religion. Later, you asked, “What do we think of that guy?” I see now that this use of “we” was an invitation to a moment of shared humanity.

Kristiana: Haha! Yeah, I don’t have much patience for the idea that anything is useless. That which makes us angry, that frustrates us, even that which we wish to dismiss—these are ideas or institutions or events that are highly useful to our development as people, and as writers. In “Thirty Nine Rules for Making a Hawaiian Funeral into a Drinking Game” I use the idea of religion—and a specific kind of missionarism—to delve into the relationships among the story’s family members, as well as their response to the loss of their matriarch. This kind of missionarism, and the missionary history of the islands, doesn’t sit easy with me, but I also can’t leave it. It’s influenced how I think, what I believe, who I am. Such a complex territory is of interest to me, and I’m often exploring similarly uncomfortable and complex territories in my stories.

Michael: In your stories we clearly see aspects of Pacific literature, feminism, identity politics. What else would you like your audience to consider? For example, in light of Hawai`i’s history—and considering the relatively small but omnipresent voice for independence—did you have a postcolonial perspective in mind?

Kristiana: Even though all the stories in the collection are set in the contemporary time period, I did a lot of historical research before writing this book. I spent days in various archives. I took graduate courses in Pacific history at the University of Michigan. I listened carefully to the stories my family had to tell, to their way of being in the world. I also listened carefully to stories from those who are non-native but local, whose families can count back several generations, often to the sugar cane plantations where ancestors came to work and decided to stay. Through all this I tried to understand what it means to claim the islands as home, no matter what race or ethnicity or culture someone is. I think, in doing this research, it helped me feel compassion for all my characters.

Part of feeling that compassion and empathy is understanding my characters’ emotional response to their world. Some are angry. They don’t have a postcolonial frame of mind; they’re still at war. They feel their nation has been illegally overthrown and taken over—which, for the record, is historically accurate. Some are grateful. They’ve found freedom in the ranch lands or the wide expanse of ocean, and no matter what is historically accurate, they’re just happy to be on these islands. Some are confused. Cameron in “The Road to Hana” is trying hard to understand Becky’s worldview: he cares for her, and he wants to be expansive enough to live in her world and his at the same time.

I hope my readers, in completing the book, understand that each character, like each person, has an individual relationship with the islands. The land. The water. The history. The politics. I’m happy to voice my personal opinions on each of these subjects in a private conversation with friends, but for the book, I stepped out of the way. Those characters who share my opinions get as much attention as those who don’t. And it’s the chorus of voices—their widely ranging opinions, their naiveties, their deep knowledge—that comes together to give what I feel is an honest view of Hawai`i: at once diverse, complex, difficult, and beautiful.

Michael: Throughout the collection, but perhaps especially in “The Old Paniolo Way” and “Wanle,” you present characters who refuse to be confined by gender stereotypes. Why include so many characters who upend expectations of gender and sexuality?

Kristiana: I am intrigued by women who enter into arenas often reserved for men—such as cockfighting—and by men who move easily within spheres traditionally dominated by women—such as nursing. I’m also curious about how such a character experiences the world. And if, despite the confidence to move into spheres where they’re not expected, other fears or uncertainties arise for them.

For “Wanle” I wanted to write a young woman who is tough, immune to a certain type of violence, and deeply connected to the male role models in her life. At the same time she has ownership over her sexuality and femininity. She’s got this core of volcanic strength, but she’s also trying to figure out who she is, how she will forge beyond the shadows cast by the men in her life. But what’s most compelling to me about Wanle is how she navigates the path to her own freedom, leaving behind not just the men and their shadows but even her past self.

In “The Old Paniolo Way,” Albert is physically strong and beautiful, emotionally open and supportive, intellectually engaging. In one moment his features are described as delicate and lovely, and in another moment his full beard becomes a sexual turn-on for the main character. I wrote Albert as a man comfortable with both his sexuality and the opposing expectations placed on him by his family. He’s found a path he feels comfortable walking, and he’s found peace. But I’m actually less fascinated by all this than the way Albert upends ideas about death. Because he’s a hospice nurse he’s had to think hard about, and witness, suffering and dying. So the humanity that Albert expresses is tied neither to his gender nor his sexuality but to who he has become from years of living and evolving.

Michael: As I mentioned, I occasionally feel haole—even foolish—when your native characters hold court against those ignorant of tradition, or those who lack the skills to navigate interactions with locals. For example, the surfer girls in “This is Paradise” speaking of tourists, claim, “They’re all white to us,” and in “The Road to Hana” Cameron and Becky debate “that sense of displacement, of never quite fitting in.” Yet it could easily be argued that most tourists have an innocent, even pure attraction to the islands and their denizens. Are there any rules you wish visitors followed when they come to Hawai`i to help them better understand the place?

Kristiana: Don’t drop in on anyone in the line-up. [Laughs.]

But seriously, I’ve surfed in Southern California and while there’s a line-up, the sense that the fastest paddler gets the wave is much more prevalent than in Hawai`i. In Hawai`i, it’s not always the person farthest out or the fastest paddler. It could be the older local who surfs that spot every morning. Better make way for Uncle! It could be the woman who likes a specific kind of shape in a wave, and the regulars let her have that wave when it finally comes through. A visitor to that break—and this has been me plenty of times!—has two choices. They can either blast in, start paddling for what they want. Or they can sit back, spend some time watching and listening. Say good morning to the regular crew. And then wait until someone gives the nod to start paddling for a wave.

The line-up is an analogy for traveling in Hawai`i, or anywhere. A couple rules might exist; for example, the person farthest back has right of way. But what’s really important is approaching people as individuals. Being open to who they are, what the space is that you’re sharing. Asking yourself, who am I in this situation? And asking them who they are.

Michael: You have lived in numerous places: Not only Hawai`i, but also New York City, Michigan, California, and now Washington state, just to name a few. With all these geographical influences,

do you plan on having your writing move beyond settings in the Pacific? Are there unique challenges you foresee?

Kristiana: My mother’s ancestors are from Norway and Germany, and our family settled in North Dakota. My next book is set on Maui, but after that I will likely turn my attention to the Dakotas. On the surface, it seems like Hawai`i and North Dakota couldn’t be more different, but the same concerns and fascinations that are in my work now will remain, no matter what the setting. I’m interested by how people fall in and out of love. I’m curious about characters who inhabit two worlds at once, who are bi-cultural, multi-racial, two-spirited. Those characters, and the way they approach the world—as well as how the world approaches them—will continue to populate my work.

Am I concerned that readers won’t stay with me because I write a book set elsewhere than Hawai`i? No. I can’t be. I can only find a story I care deeply about, and characters I love, and write that story and those people to the best of my ability. After that, the rest is out of my hands.

Michael: Who are the writers who have most influenced you? I see hints of Joyce in the understated but understood relationships. I see Annie Proulx in the sparse density of your prose. I see Richard Wright and W.E.B. Dubois in the way you present injustice in such a matter-of-fact way. Have any of these writers, in fact, been a conscious influence on you?

Kristiana: I like writers who are fearless, who aren’t afraid to set a story ablaze. Richard Wright and Sherman Alexie are great examples of this. They bare their teeth at the reader, refuse to hold your hand, but if you keep reading, the reward is a level of honesty that lands on the border between pain and beauty. Annie Proulx writes at this point; plus I love how landscape becomes character is her work. Katherine Mansfield, for all the lightness at the surface of her stories, is not afraid of turning on her characters and holding them up for the reader to judge. In other words, she doesn’t protect her characters, doesn’t try to soften them or make them better humans than they are.

Stylistically, Katherine Mansfield again. I’d love to claim Joyce, but then I’d feel embarrassed I claimed Joyce. Michael Ondaatje because I adore his rich imagery, the almost surreal way he casts a flashlight on a moment of darkness, and a character, a frozen pond, a boat of misfits is illuminated.

Michael: I had not thought of Alexie and Mansfield, but I see it now. I also see Twain—in your gift for dialect, your condemnation of imperialism, and especially your use of the Pacific Ocean, which, like Twain’s Mississippi River, reverberates within every character and act.

Kristiana: Thank you. I’d just like to be as funny as Twain. He balances humor with such sharp commentary. That combination is a model to follow.

Michael: You offer significant context clues to lighten the load of the reader—especially with, but not restricted to, the use of pidgin (Hawiian Creole). How conscious were you of this strategy and were you ever afraid of giving too much, or not enough, context to your readers?

Kristiana: Several people have asked why I didn’t include a glossary. My elderly aunts, for example. They are very dear and they were concerned that readers wouldn’t understand Harrison, the father in “The Old Paniolo Way,” because his pidgin is so thick. But I think that’s part of who Harrison is, and that’s how he interacts with the world, and I didn’t want to dilute that visceral experience for the reader. I could have included a glossary or footnotes, but when you meet a man like Harrison, you don’t have a glossary or footnotes. I don’t want Harrison—or any of the characters, or the place of Hawai`i—to be made foreign by a glossary or guide book. I want the reader to feel inside this experience.

I added context clues, enough that a reader has a gist of what he’s saying even if individual words are lost. And I placed that story at the end of the collection, at a point where readers would have already encountered lighter forms of pidgin. After that I let the reader come to the story.

Michael: What can you tell us about your next writing project? What challenges are you facing? Without ruining any surprises, what can you tell us to expect that will raise our eyebrows?

Kristiana: Well, I don’t know what raises every reader’s eyebrows, but I can work on something!

My current project is a novel set on Maui. It covers two time periods, and follows several generations of a Hawaiian family as they fight a water rights dispute with one of the largest sugar cane plantations in the islands. I like to think of it as Edward P. Jones’s The Known World meets Chinatown. There’s a historical portion to the book; there’s corruption and scandal. But here’s where I think things get really explosive: Not every family member is on the same side of the dispute. This seems like a simple statement, but I think that it can be a hard truth for a close-knit group of people to realize: Not everyone is following the same path. Still, the community, the family, can survive this conflict, and will, and must.

Michael: Naturally everyone will want to know how much of your work is autobiographical. Can you speak to this? And what do we learn about Kristiana Kahakauwila the person from the voices of your narrators?

Kristiana: I often enter into a story by starting with a real object or place and then fictionalizing its significance or relationship to the character. For example, in “This is Paradise,” the description of the signs on the beach that opens the story is exactly what I saw when a large swell hit the south shore. But the characters’ response to that, the addition of a young woman in a polka-dot bikini, the voice—that’s all fictionalized. Similarly, in “Portrait of a Good Father,” the photograph that opens the story is based on a picture of my own dad. The real photograph hangs in my parents’ office, and I grew up looking at it because the image is arresting and my dad is quite young and handsome in it. So I used that real image, and the act of describing it, as a way into the first scene of the story, except instead of me looking at the picture, it’s another young woman, one who has watched her family fall apart. I started writing that story by wondering how this woman—whose family situation is wholly different from mine—might react to a similar portrait of her dad.

I think the reader learns little about Kristiana Kahakauwila the person from the voices of my characters. That said, I think one can learn a lot about who I am as an author. I like experimenting with point of view and perspective. I often wonder—in story life and real life—how people around me are reacting to the same object or event or person that I’m reacting to. I’m curious about how we become the people we are, how our histories affect the ways we see the world and live in it. That curiosity is explicitly explored in “The Road to Hana,” with the tension between Becky and Cameron, but it’s implicitly the driving force behind many of my characters’ relationships with one another.

Actually, I guess you do learn a lot about me from those voices. You learn that I’m looking at you and thinking, how did you become who you are? What do you think of this picture or this street or this surf break? I love that people can have the same stimulus but respond with completely different emotions and thoughts. I am constantly amazed by that and I want to understand it.

I suppose you’ll never want to have dinner with me again. You’ll keep thinking, Is she trying to get inside my head?

Michael: It depends. Who’s buying?

Kristiana: Ha! You are!

Michael Kelley was born and raised in Philadelphia and now lives in St. Louis, where he teaches English and Film at Chaminade College Prep. He earned a Master’s Degree from St. Louis University and another from the University of Missouri. For the last three summers he has taught English at Chaminade University in Honolulu. He recently published an academic article on Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home in Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (UK). He is happily the father of two adult children.

Kristiana Kahakauwila, a native Hawaiian, was raised in Southern California. She earned a master’s in fine arts from the University of Michigan and a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature from Princeton University. She has worked as a writer and editor for Wine Spectator, Cigar Aficionado, and Highlights for Children magazines. She taught English at Chaminade University in Honolulu. An assistant professor of creative writing at Western Washington University, Kristiana splits her time between Bellingham, WA, and Hawai`i. This is Paradise has been chosen as a Barnes & Noble Summer 2013 selection of the Discover Great New Writers program as well as for the Target Emerging Author program.

Visit Kristiana Kahakauwila’s site to learn more about her and to purchase This is Paradise.

“This Is Paradise, by Kristiana Kahakauwila, navigates an ocean of tension between tourists and islanders in paradisiacal, paradoxical Hawaii. Gritty, haunting, and suspenseful.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“[A] sparkling debut story collection . . . A writer with one foot in the native Hawaiian community and the other in the mainland mainstream gives us an edgy, unmistakably authentic glimpse of the harder side of island life. Kahakauwila captures in six related stories the striving lives, colorful pidgin dialect, and varied relationships that anchor and challenge her strikingly drawn characters.” —ELLE

“[T]his debut collection promises a tour of the real Hawaii. . . . Ms. Kahakauwila illuminates racial and class tensions and the guilt of leaving home for the mainland.” —New York Times

Vividly imagined, beautifully written, at times almost unbearably suspenseful—the stories in Kristiana Kahakauwila’s debut collection This Is Paradise are boldly inventive in their exploration of the tenuous nature of human relations. These are poignant stories of “paradise”—Hawai’i—with all that “paradise” entails of the transience of sensuous beauty. —Joyce Carol Oates

[printfriendly]